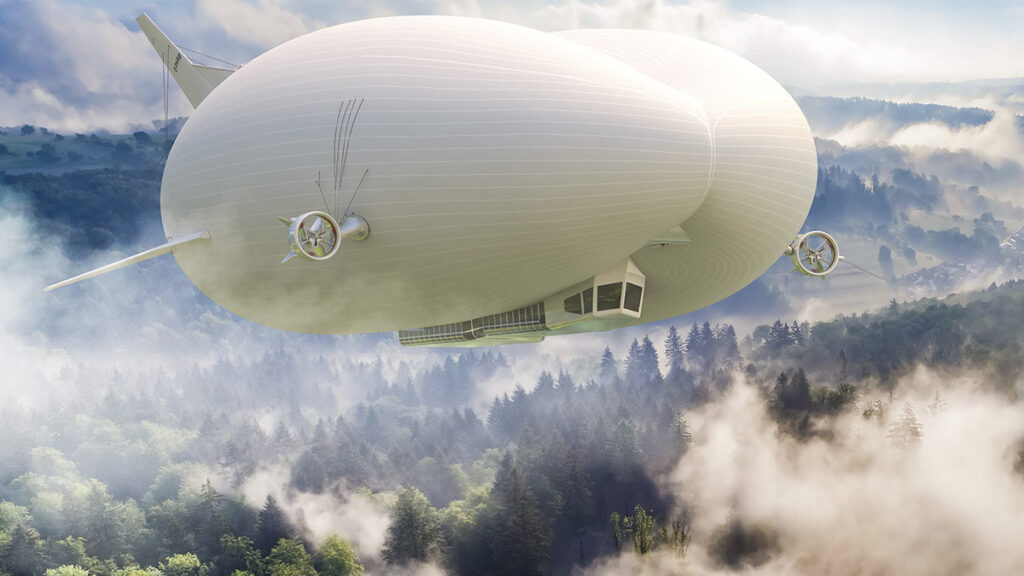

Looking at the Airlander 10, it is difficult to not feel a little sceptical – the aircraft looks more like something from a sci-fi movie than the ride taking you to your next weekend destination. However, after a talk with Hybrid Air Vehicles (HAV), the company behind the eye-catching aircraft, Discover CleanTech is more than ready to get onboard.

At the first sight of the Airlander 10, you may struggle to determine if it belongs in the future or in the past – perhaps most of all it looks like the mode of transport a fantastic team of cartoon heroes would use in a quest to save the world. And in a way it is. Or at least, as Mike Durham, chief technical officer at HAV more modestly says, it is the creation of a team that “is keen to be at the forefront of change”.

“The aviation industry has to get its act together and start dealing with the environmental challenges the planet is facing,” he stresses, adding: “It is important that we understand that and understand that passengers won’t stop flying – it’s become part of what it means to be human.”

Indeed, the growing aviation industry may benefit from the Airlander’s unique features which, by combining the buoyancy of helium with aerodynamic lift and vectored thrust, reduce carbon emissions to one quarter of a regular aeroplane. For the Airlander 10 model as it is now, with four combustion engines, the goal according to Durham is to have a zero-emission aircraft in the air by 2030.

Not an airship, not a plane

To most people, the characteristically large hull of the Airlander is likely to evoke images of the airships of the past; that is not what it is, however. Whereas an airship typically operates very close to equilibrium, meaning they are neither heavier nor lighter than air, but buoyant, hybrid air vehicles are typically heavier than air and, though much bigger, the shape of the hull is more like that of an aeroplane, designed to produce an aerodynamic lift. This means that, unlike airships, the Airlander can carry more weight than is offset by its lifting gas, helium, and have greater flexibility and manoeuvrability. Compared to an aeroplane, the benefit is that three quarters of its weight is being carried by helium, meaning that no fuel energy is required to keep it up, whereas an aeroplane has to keep pushing itself up.

Currently, the baseline Airlander 10 has four combustion motors, which results in an aircraft that produces just 25 per cent of the CO2 emission per passenger per kilometre compared to an aeroplane, but as soon as the aircraft is type certified, it will go into a modification programme to remove two engines and replace them with hybrid-fuelled electric propulsion motors, reducing emissions by 90 per cent compared to a standard aeroplane. To this end, HAV has been working with Collins Aerospace and the University of Nottingham (UoN) to develop a suitable electric propulsion technology. The hybrid Airlanders are scheduled to be in the air in 2026, and by 2030, the plan is to go fully electric, reducing emissions to zero.

The large volume of the Airlander’s hull is part of the reason why the aircraft provides an ideal platform for electric propulsion powered by hydrogen fuel cells. “One of the challenges of electrification is how to store enough energy to reach the desired range, and compared to aeroplanes, we have much less volume constriction and hence more space for the storage of hydrogen fuel,” explains Durham.

Another advantage, of course, is the overall low energy consumption of the aircraft, allowing longer ranges on less fuel. Currently, the Airlander 10 has a range of up to 3,000km, can stay in the air for five consecutive days, and carry a load of up to ten tonnes.

In city to city transport, the Airlander could offer many advantages compared to aeroplanes.

Comfort and a clean conscience

It all sounds almost too good to be true, and indeed there is one aspect where the Airlander will never be able to compete with a regular aeroplane, and that is speed. While the Airlander only produces a quarter of the CO2 of a plane, it also only travels at a quarter of the speed, around 120-30 km/hr. This means that when it comes to passenger transport, the aircraft will be most advantageous on shorter routes. “You have to pick the routes,” stresses Durham. “One of the benefits is that we don’t need to operate from a conventional airport – we can operate from a green field or water. We see our mobility as a sort of ferry or train service, and that gives us an opportunity to reduce the time we are on the ground and the time it takes for passengers to get to and on the aircraft. But probably we are best suited to passenger operations below 200-300km distances; that would mean you would be in the air for two or three hours, but you would not spend time in an airport taxying.”

When looking at city centre to city centre transport time, tests show the Airlander to be only a little slower than a plane, but on the other hand, the CO2 footprint of the journey is significantly reduced, or even eliminated.

The Airlander will be slower than regular aeroplanes but will provide passengers with a premium experience and a significantly reduced – with time even eliminated – CO2 footprint. Photo: Hybrid Air Vehicles Ltd/Design Q Ltd

He goes on to stress that the form of city centre to city centre transport that the Airlander can offer will be especially well-suited to cities located next to water bodies on which the Airlander can land. As the Airlander needs very little in terms of landing infrastructure – a plain area of around 600 metres to take off and land on and mast to moor to are all it takes – there is also a reduction in terms of the CO2 footprint of the built structure compared to the runways and airports of aeroplanes.

Of course, a clean conscience may not be enough to persuade all passengers, but even travellers who perhaps don’t pay much attention to their carbon footprint may still be swayed by the Airlander’s charms. On top of being much more CO2 efficient than planes, it is also more comfortable. Travelling at a typical altitude of 6-8,000 feet, the aircraft is not pressurised, which provides a more pleasant and comfortable travel environment. Moreover, as the engines and propellers of the aircraft will be about 60 metres away from passengers, the noise level will also be significantly reduced. Lastly, the aircraft’s spacious payload structure – the full-length main cabin (excluding flight deck) comprises 2,100 square feet of floor space – offers air operators great flexibility in terms of layout. “In air, passengers will also have a tremendous view of the ground, with panoramic windows, and there will be no vibration and little noise. It will be a very serene way of flying, and space wise it will be much like a premium environment, so again you might be in the air a little longer, but it will be a much more pleasant environment to be in,” stresses Durham.

Chief technical officer, Mike Durham, has been with HAV since the company’s start in 2007 and has been work ing with lighter-than-air aircrafts for around 30 years.

When can we get on one?

If you still think the Airlander sounds like something from the future, rest assured that it is very real, and soon it should be cruising the skies of Europe. Recently, it made headlines in the British and Spanish press when the Spanish Air Nostrum Group reserved ten hybrid Airlander aircrafts for delivery in 2026. And, according to Durham, the company is negotiating with a number of other customers in experiential tourism and air transport. He also foresees many other applications for the aircraft. For instance, while the Airlander has little potential in regard to long-haul passenger transport, the ease with which the aircraft can be scaled up in size allows for interesting prospects when it comes to the transport of freight. “We have seen some opportunities from that sector, and we are talking to businesses about a larger version of the Airlander, the Airlander 50, which will carry 50 tonnes of payload instead of 10. It will be even more fuel efficient than the 10 because the size of the aircraft does not increase five times, that’s one of the oddities with lighter-than-air – the bigger it is, the more efficient it is,” explains Durham.

The chief technical officer even sees a potential for an even bigger aircraft to start continental freight as an alternative to boat transport. “As it is now, you either have to fly it in an expensive aeroplane, in which case it will arrive in six hours, or send it with a boat, which means it will arrive in about a week. With the Airlander, there’s the opportunity of creating a middle market, where you get there in a day or a day and a half. And unlike passengers, most freight is happy to spend a couple of days in the air,” he jokes.

Among other suggested applications for the aircraft, which flies at a maximum height of 20,000 feet, are weather surveillance, security surveillance and defence. Indeed, with the aircraft’s many unique characteristics, it is, says Durham, just up to the aviation industry how to best make use of it. “Our headline ambition is basically to deliver an aircraft that is substantially more efficient with regard to energy use than aeroplanes. Beyond that, it is for the aviation industry to decide how they want to utilise us.”

The Airlander above Cardington, Bedfordshire, where it has been tested through several years.

The history of the Airlander:

The history of the Airlander goes back to 2001 when the original hybrid aircraft design, SkyCat, was patented. In 2007, SkyCat was acquired by HAV, and in 2009, the company was awarded a contract to design an aircraft for the US Department of Defence’s Long Endurance Multi-Intelligence Vehicles programme. This led to the development of a full-size prototype which flew for the first time in New Jersey in 2012. At the premature dissolution of the programme in 2013, HAV decided to purchase the demilitarised aircraft and disassemble and transport it to England. During 2014, the company undertook an extensive work programme to reclassify the prototype as a civil aircraft, named Airlander 10. Over 500 modifications were made during the course of the next few years, and on 17 August 2016, Airlander 10 successfully completed its maiden flight in the UK. During initial test flights, a too steep landing and a mooring accident caused damage to the first prototype.

The HAV team was, however, not deterred and in 2018, the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) awarded Hybrid Air Vehicles Ltd a Design Organisation Approval and a Production Organisation Approval, meaning the company is approved to design and manufacture an aircraft. In March 2022, the EASA released the certification basis for airship-based aircraft designs developed in collaboration with HAV and other European manufacturers of buoyant aircraft. This had to be done as no certification standards existed for this type of aircraft. The standards will allow HAV to work towards a Type Certification, which certifies the aircraft’s ‘airworthiness’, and is a prerequisite to putting the Airlander 10 into production. This typically takes between three and five years, depending on the size and role of the aircraft, but as HAV has already completed much of the flight test programme and closely collaborates with the regulators, it anticipates that the Airlander will be in service from 2026.

Photo: Hybrid Air Vehicles Ltd/Design Q Ltd