A European research team led by Imperial College London has brought the hydrogen economy closer to reality with a technology breakthrough in fuel cells.

The breakthrough involves creating catalysts from iron instead of more expensive platinum, potentially paving the way for much cheaper fuel cells that can be applied to many more situations.

Fuel cells are key for the energy transition, allowing low-carbon fuels such as hydrogen to be turned into electricity.

Polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells, the most promising technology for powering electric trucks and other vehicles, can combine renewably produced hydrogen with oxygen to create electricity, with water vapour as the only by-product. To do this, the fuel cells use catalysts that have traditionally been made of platinum, a rare and expensive metal.

“Currently, around 60 per cent of the cost of a single fuel cell is the platinum for the catalyst,” says the study’s lead researcher, Professor Anthony Kucernak from the Department of Chemistry at Imperial.

“To make fuel cells a real viable alternative to fossil-fuel-powered vehicles, for example, we need to bring that cost down.”

Imperial’s catalyst design “should make this a reality,” he says, “and allow deployment of significantly more renewable energy systems that use hydrogen as fuel, ultimately reducing greenhouse gas emissions and putting the world on a path to net-zero emissions.”

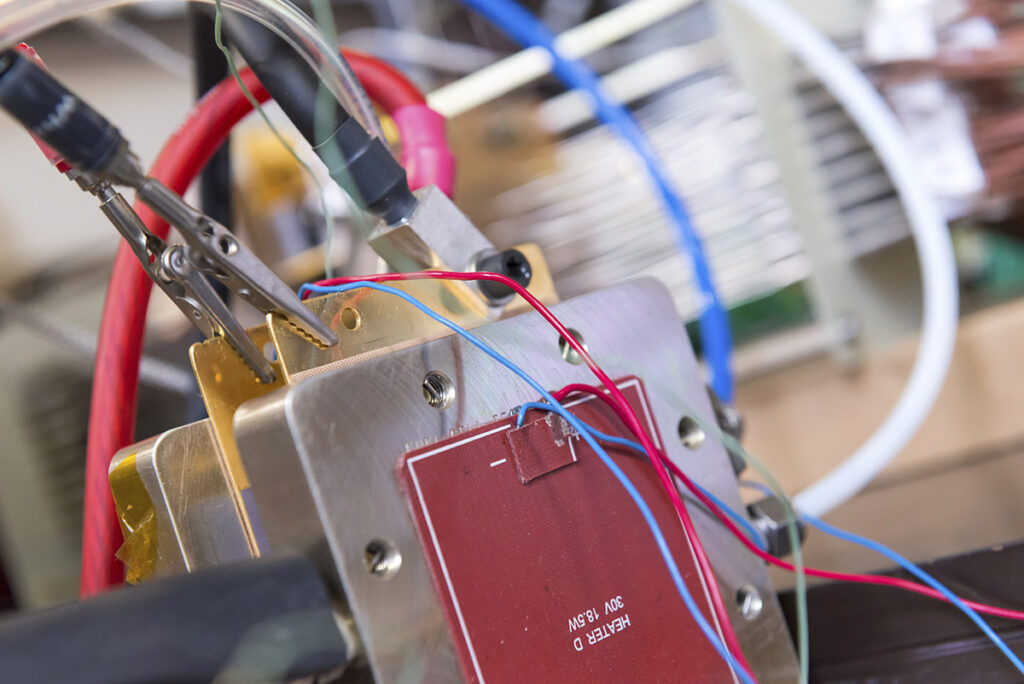

Imperial says the researchers has created a catalyst from iron, carbon and nitrogen, all materials that are cheap and readily available, and shown it can be used to operate a fuel cell at high power.

The development is important because limited platinum reserves could drive up the cost of fuel cells just as they become more important for decarbonisation.

There are only thought to be around 70,000 tonnes of platinum reserves in the world, more than 90 per cent of which are in South Africa.

The danger of having to rely on such a rare element was highlighted as long ago as 2008, when Cordelia Sealy of the Institute of Physics in London, UK, noted that the cost of the platinum in a fuel cell vehicle would be higher than the cost of an entire petrol engine.

“The high and volatile price of platinum alone could be a potential showstopper for fuel cells in any truly mass-market application such as transportation,” she said.

Keeping fuel cell costs down will be important for sectors that are relying on low-carbon hydrogen as a substitute for fossil fuels.

“In transport, hydrogen is the most promising decarbonization option for trucks, buses, ships, trains, large cars and commercial vehicles,” states the European Commission-funded Fuel Cells and Hydrogen 2 Joint Undertaking in its 2019 Hydrogen Roadmap Europe report.

The Imperial College news comes shortly after an Australian company called Hysata claimed to have found a way to cut the cost of making the low-carbon hydrogen that will be needed for fuel cells as reported previously in Discover Cleantech.

Elsewhere, there are also moves to use iron in batteries, in place of other rarer, more expensive materials such as cobalt.