Airborne wind energy: flight of fancy or grounded idea?

BY JASON DEIGN

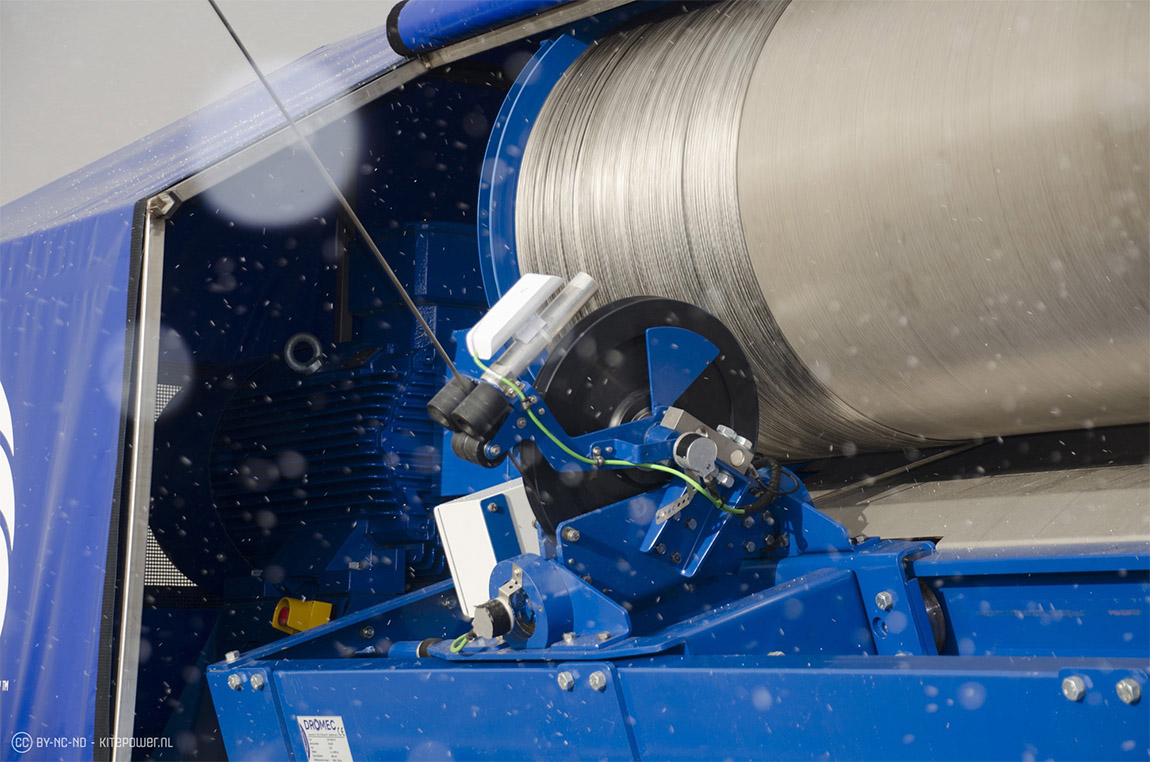

Photo: Kitepower/Henri Werij

The eastern coast of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean is home to what at first sight might seem like a kite maker’s folly. On windy days, a 120-square-metre red-and-white kite may be seen soaring and dipping over the sugar canes on the tropical island.

Yet the kite, designed by a German company called SkySails Power, is in fact the first commercial example of a form of renewable energy that proponents believe could one day help power not only remote islands but many other locations besides. SkySails is one of a select group of companies pursuing what is known as airborne wind energy, which relies on kites or gliders to access the strong, constant winds high above ground – beyond the reach of conventional turbines. Today’s technology encompasses two main power-generation concepts.

The SkySails Power airborne wind-energy generator in action. Image source and rights courtesy of SkySails Group.

In one, a flexible kite pulls a tether which unwinds from a drum, driving a motor in the process. When the tether is fully unwound, the kite is reorientated so it can be brought back to its starting position with minimum effort and the process starts again. The second concept involves fitting rotors to a rigid glider tethered to the ground. The glider does loops in the sky, creating an airflow that turns the rotors and produces electricity. Since the electricity is generated in the air rather than on the ground, this idea is dubbed ‘fly-gen’.

The jury is still out over which mode of operation is most effective, but the evidence points to rigid fly-gen gliders falling behind in the race for commercialisation. Fly-gen was the technology of choice for Makani Power, a company that brought airborne wind energy to mainstream attention after being incorporated into X Development, a research and development subsidiary of the tech giant Alphabet, which also owns Google.

Despite Alphabet’s blank-cheque patronage, Makani folded after 13 years of development, leading to questions over the future of the whole airborne wind-energy segment. The reasons for Makani’s demise have been hotly debated. One of the more prosaic explanations is simply that the project was favoured by Google and Alphabet’s founders, Sergey Brin and Larry Page, and when they stepped away from the day-to-day running of the businesses in 2019, the support for airborne wind energy evaporated.

However, X boss Astro Teller also admitted that achieving commercial viability with the technology “is a much longer and riskier road than we’d hoped.”

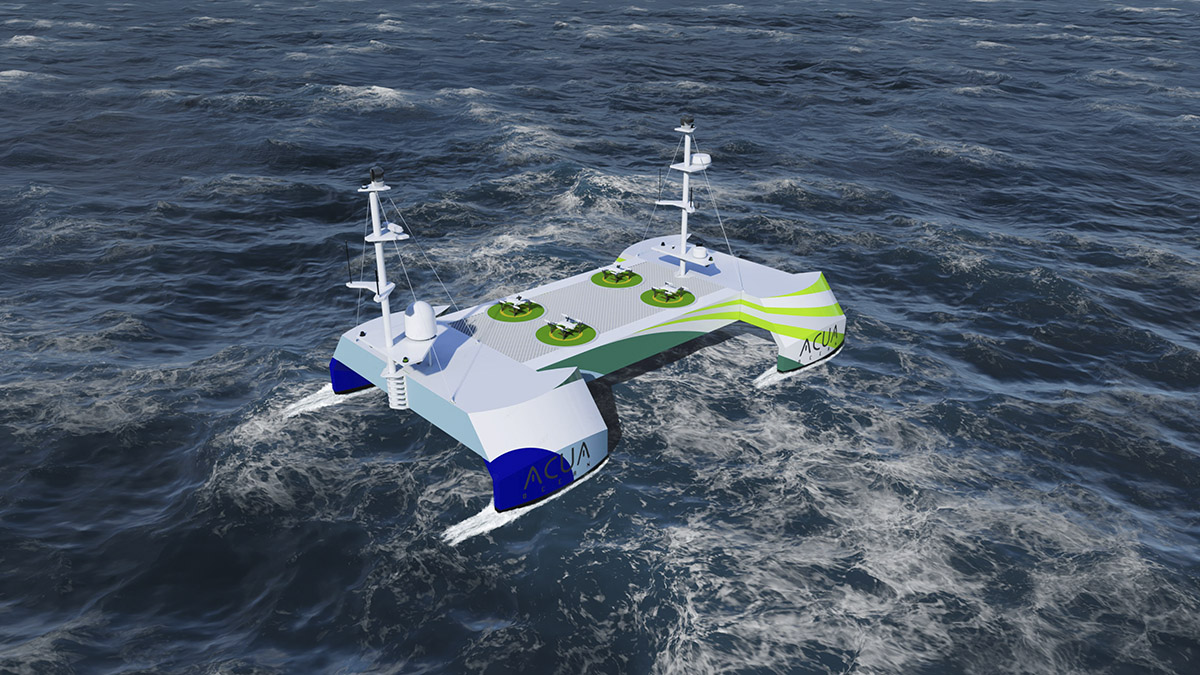

Photo: Kitepower

A longstanding challenge

Maximilian Isensee, co-founder and chief executive of German firm Kitekraft, which is developing a system like Makani’s, says technology advances are helping overcome some of the challenges that Makani may have faced. “We have a digital twin of our system now,” he says, “that can do everything the kite does in software instead of flying.”

Kitekraft is working on smaller machines than Makani’s, which could help with development. Yet it is also true that most fly-gen hopefuls have dropped out of the market. “From what we know, we are only one of two companies now doing the fly-gen approach,” Isensee says.

None of this is to say that the alternative kite-based approach is easy. The idea of using kites to generate electricity goes back at least four decades and yet progress towards commercialisation remains minimal. Besides the SkySails installation in Mauritius, the nearest the airborne wind-energy sector has got to a commercial project is a pilot on the island of Aruba in the Caribbean, operated by the Dutch Ministry of Defence using a system developed by Kitepower of Delft in the Netherlands.

Despite this, the idea of pulling electricity out of the air continues to attract adherents – and money. In Europe, a project called MegaAWE has injected more than 12 million euros into the development of an airborne wind-energy test site in Mayo, Ireland. Flights are due to start this year. And an industry body called Airborne Wind Europe has 15 members including technology developers from Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Switzerland, the UK and the USA, plus academic representation from TU Delft, Politecnico de Milano, RWTH Aachen, and the University of Stuttgart.

Photo: Kitepower

If they can get the technology to work commercially, then it “makes large-scale wind-energy potential accessible in altitudes up to 500 metres,” says Kristian Petrick, Airborne Wind Europe’s secretary general. “There is no other technology able to tap into these vast renewable energy resources. It also enables increased energy generation per square kilometre, at lower carbon intensity, compared with other renewables. And, eventually, at lower cost.”

To make the technology competitive with traditional wind energy, consultancy firm BVG Associates estimates the industry might need five billion euros of public funding over the next decade and a half. At less than a fifth of what the UK is paying for its latest nuclear reactor, that figure may not be as big as it seems – and airborne wind energy’s sky-high benefits could be worth it.

Kitepower in Aruba: A Kitepower Falcon airborne wind-energy system being tested by the Dutch Ministry of Defence in the island of Aruba. Image source and rights: Airborne Wind Europe.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Receive our monthly newsletter by email