Microplastics – it’s not just about the environment

By Signe Hansen

Due to decades of unmitigated plastic pollution, microplastics are, today, everywhere – in our waters, in our food and even in our blood.Photo: Istock

Microplastics are everywhere – in our waters, in our food and, new research shows, even in our blood. The good news is, however, that if we stop polluting our environment with plastic waste, improvements could be seen within a lifetime.

It is rare to find something that everyone can agree on, but that microplastics are bad is one such rarity. The result of fragmented larger plastic items and products such as plastic microbeads, microplastics have infiltrated every part of our environment.

Recently, a study by scientists at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam in the Netherlands shocked the world by proving that even the blood from 17 out of 22 anonymous blood donors contained different kinds of plastic particles.

This comes as no great surprise to Win Cowger, an environmental scientist at the Moore Institute for Plastic Pollution Research, a non-profit organisation in California. Specialising in the transport and fate of trash in watersheds and river flow, Cowger has made it his cause to make data on microplastics more accessible through online hubs for plastic pollution research.

Environmental scientist Win Cowger.

“It is essential for us to understand the problem and be informed about the risk; if there is no data accessible, I don’t know if I am being exposed to microplastics,” he stresses. “It is important to make sure that people are realising that they’re being exposed to this stuff too.

Of course, we all think the fish in the ocean are important, we want to see the sea turtles thrive, but it is important to also be aware that we are not off the hook ourselves – when we are polluting the environment, we are polluting ourselves.”

Giovanna Laudisio, a researcher from the University of Bath in the UK and the CEO and co-founder of Naturbeads, agrees; microplastics are everywhere, also in products we would never think of as containing plastic. Since starting Naturbeads, which has developed a biodegradable alternative to plastic microbeads, she has been contacted by manufacturers from all sectors.

“Cosmetics are just a small part of the problem, plastic microbeads are used in everything – paint, coatings and products in oil and gas. We have been contacted by companies making all kinds of consumer products – leather bags may have a protective coating containing microbeads, even pillows can have microplastic in them.”

Photo: Istock

Assessing the size of the problem

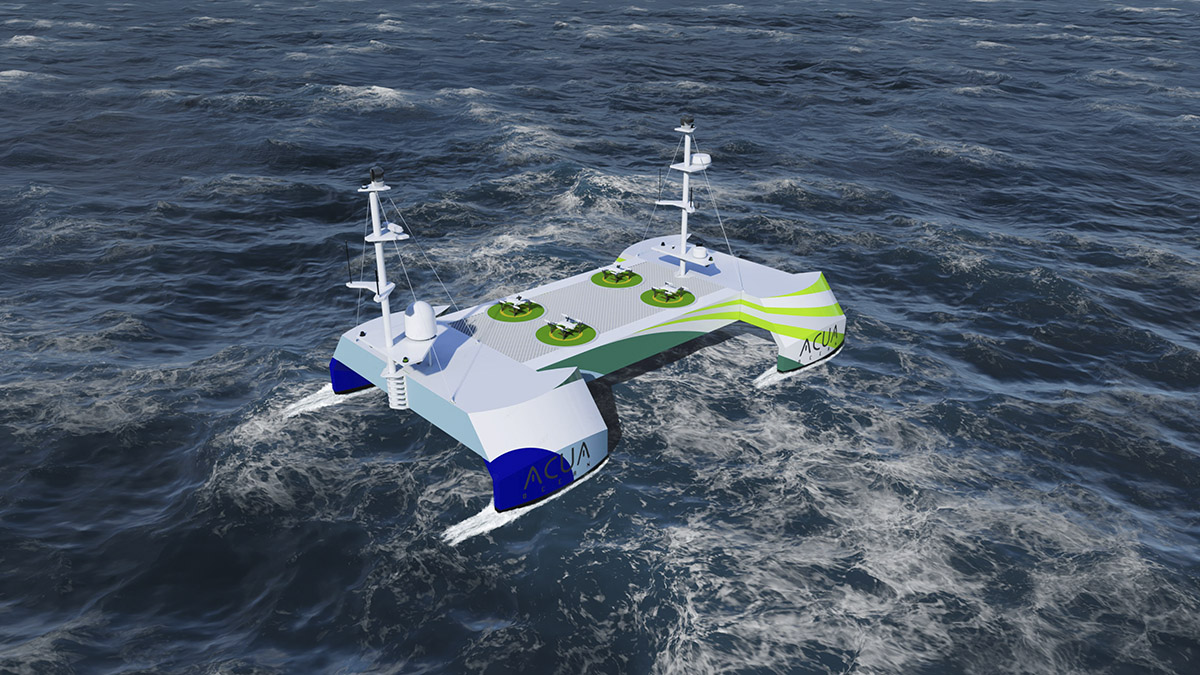

As part of the Moore Institute for Plastic Pollution Research, Cowger is working in a number of collaborations to assess microplastics exposure in water bodies. One of the projects he is excited about is the development of sensors to track the exposure in oceans and rivers.

“There are a lot of people working in this space; it’s very challenging,” he explains. “You have to float water through a device and then you have 100,000 of particles and have to identify and distinguish if it is plastic or not.”

The sensors would allow researchers to save much time in the collection and analysis of samples and thus make it easier to scale up data collection to assess the scale of the problem. Furthermore, analysis can reveal the prevalence of different kinds of plastic and thus the risks posed to the health of humans and their environment.

“Some types of plastic are certainly more harmful than others; the polymers that plastic is made of are really diverse,” explains Cowger. “Some are made of things that are known to be toxic, such as polystyrene. Styrene is known to be toxic; they turn it into polystyrene and the idea is that it is then not toxic.

But findings are contradicting this, and whenever you have fluorinated compounds, that is toxic; little molecular elements can break off when drinking hot drinks, for instance. It is bad for you, and the environment too.”

The good news

While Cowger is enthusiastic about the research done in his field, when it comes to methods to remove microplastic from water bodies, he is less optimistic. “Once it is in water bodies, as far as I know, there are no methods developed to remove it. Something like a Mr. Trash wheel is not going to work with microplastics; they will just go straight around it,” he says.

“Mostly, it will be in the sediment of the ocean and to clean that up you would have to extract the plastic, you would need to dredge the ocean! Obviously, that would be more harmful than the microplastics.”

There is, however, some good news. Because while plastic can last for centuries in perfect conditions, many natural environments will eventually break it down. “Over time, if we weren’t actively polluting at a high rate, the ocean would have the capacity to break down particles that are already there,” says Cowger.

If we stopped tomorrow, when would we see a change? I don’t know for sure, but in a lifetime. If we stop polluting today, we would see some benefits in a single lifetime, just because the ocean is capable of degrading plastics and turning it into a state where it’s not harmful.”

Moreover, some types of plastic are much faster to degrade than others. PHA plastic, plastic made from polyhydroxyalkanoates, a naturally produced biopolymer, for instance, is likely to degrade in less than two years.

“Even though it breaks into microplastics it is going to degrade really fast – the idea is that if we can get things to degrade within a year or two, then that is not of so much concern in terms of microplastics that accumulate in the environment,” explains Cowger.

However, there are still market obstacles to PHA plastic being used at a large scale; price and compatibility with existing production tools are among them.

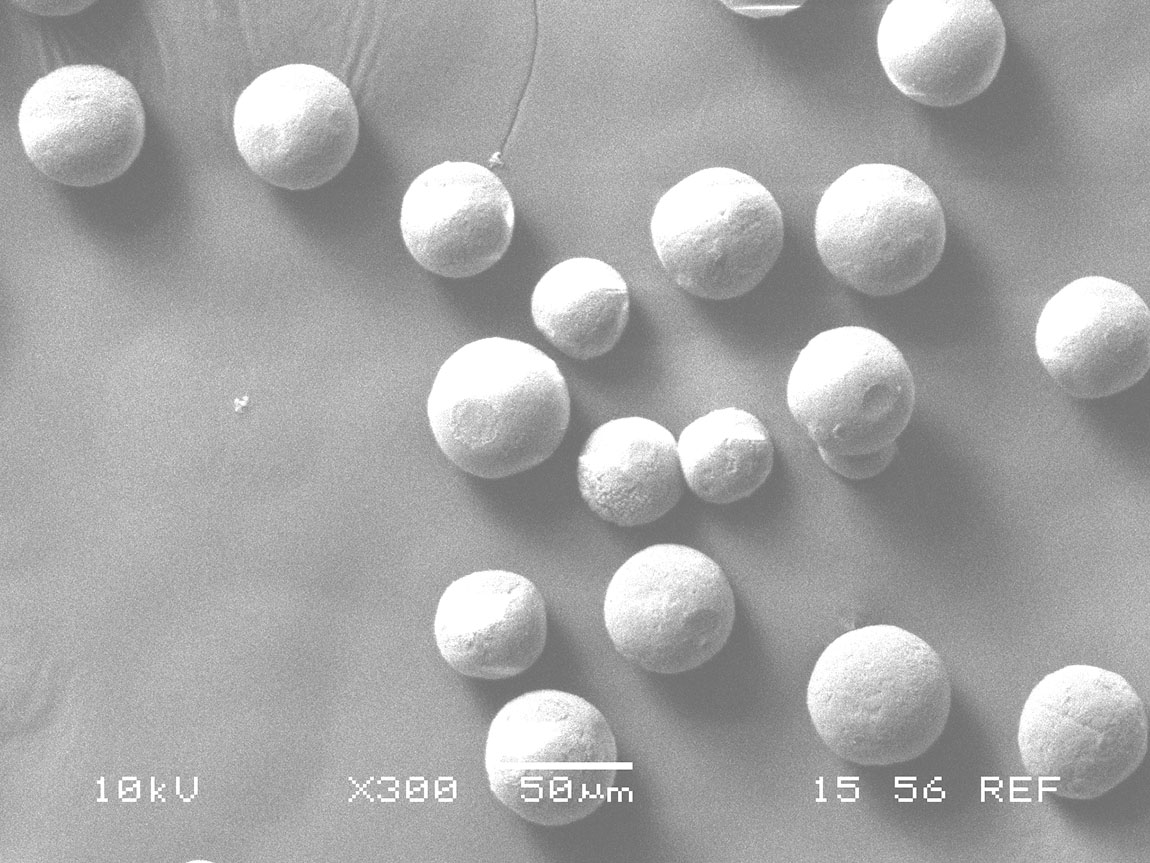

With properties matching those of plastic beads, Naturbeads, a natural and biodegradable microbead, can help solve the issue of microplastics pollution.

Replacing the sources of microplastic

One of the best-known types of microplastics is perhaps the plastic microbeads used in many cosmetic products and from there washed straight out into our water bodies. While many nations have, by now, banned, or partially banned, the use of the beads and other primary microplastics (plastics that start up as microparticles), others, including the EU are still to enact legislation, and thousands of tonnes of microbeads are thus still entering the water bodies.

“Many people ask – why not just remove the plastic beads from products, but these plastic microbeads form a function,” explains Laudisio of Naturbeads. “If you remove it, you have to replace it with something else and the problem is what to replace it with.

Naturbeads is an award-winning spin-off company from the University of Bath.

It is easier with body scrubs where there are many products like crushed nuts or seeds that can replace it, but these are not spherical, and for things such as wrinkle cream or sunscreens, you cannot use them. You need something that provides a smooth texture, something perfectly spherical of very small dimensions, very narrow particle size.”

Made in biodegradable cellulose, Naturbeads is one such product. While the product is very stable in water, it will, when left in the environment where microorganisms will attack it, biodegrade in 28 days.

Now, the challenge remains for the university spin-off to scale up production to match the demand from the market. The company is hoping to secure investments that will allow them to build a demonstration plant that will bring production to 20-25 tonnes per year by 2023.

Microplastics are solid plastic particles (typically smaller than 5mm) composed of mixtures of polymers and functional additives. They may also contain residual impurities. Microplastics can be unintentionally formed when larger pieces of plastic, like car tyres or synthetic textiles, wear and tear. But they are also deliberately manufactured and added to products for specific purposes, such as exfoliating beads in facial or body scrubs. [source, ECHA European Chemical Agency]. To explore more of the work of the interviewees of this feature, visit: www.naturbeads.com www.openspecy.org

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Receive our monthly newsletter by email