The Climate PI: the organisation battling the climate crisis with big data

BY SUNNIVA DAVIES-ROMMETVEIT, MADE IN PARTNERSHIP WITH THE CLIMATE PI

The Climate PI (Planetary Intelligence) combines state-of-the-art AI with nature-based, technology-based and social solutions to figure out which solutions need to be scaled, where and in which combination. Discover CleanTech learns how the firm harnesses big data to address some of the biggest challenges our planet faces.

“All of the solutions that we need to reduce emissions and rejuvenate nature whilst improving living standards, are already out there,” explains Jennie-Marie Larsen, chief executive of machine learning and climate solution recommendation engine company The Climate PI. “The problem is that all of these innovative solutions are fragmented around the world – stuck in silos – meaning that progress isn’t shared with the rest of the world, and we don’t apply those solutions to similar locations across the world.”

Getting to net zero before 2050 requires high-impact solutions and unprecedented international and intercorporate cooperation. Yet, knowing what solutions to apply, where and how requires an understanding of not just climate science – complex in and of itself – but of the economical, political, sociological and psychological, real-world changes that such green transitions could evoke.

Larsen points to recent well-meaning but mismanaged attempts to ‘green’ cities and transition away from fossil fuels. London’s Liveable Neighbourhoods scheme, which provided funding to London boroughs to implement green solutions, was recently paused due to backlash from some Londoners. “Some solutions simply weren’t workable for communities,” Larsen explains. “Many smaller streets in London became pedestrianised, but that simply meant a lot more traffic and pollution on London’s busier roads.” A similar situation happened in France, Larsen adds, when French president Emmanuel Macron raised Diesel prices in an attempt to discourage driving: those most hit were the poorest in society who can’t afford the slightest increase in cost of living, who don’t have access to public transport because they live in rural areas, and this led to country-wide protests.

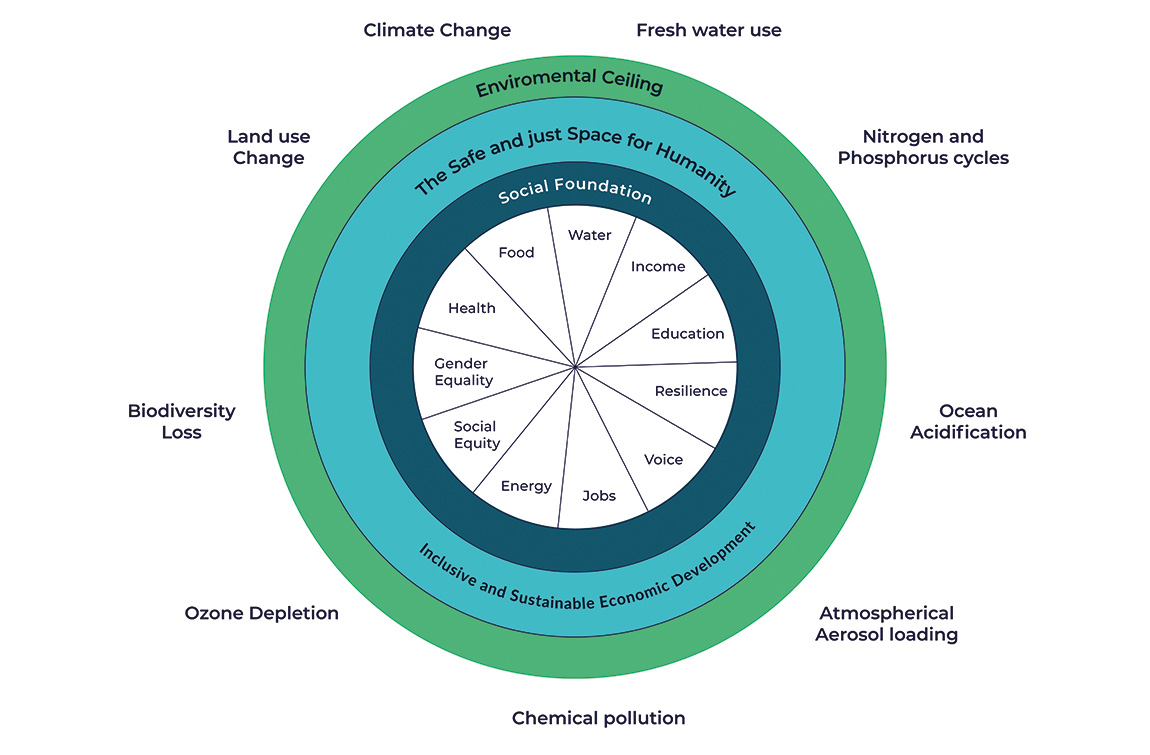

Economist Kate Raworth’s ‘Doughnut Economics’ offers a vision of what it means for humanity to thrive in the 21st century.

The reason for these strategic failures is that the vast majority of decision makers are unaware of many of the solutions available to help drive down the sources of emissions and increase the capacity of natural carbon sinks. Climate PI will provide access to hundreds of climate solutions and, most importantly, associated data on the projected impact of each solution. Larsen explains: “We want to use local IoT and macro-environmental data combined with machine learning to understand what solutions are working, in which combination and in which types of environments – so that we can recommend a suite of the best-fit solutions for similar parts of the planet.”

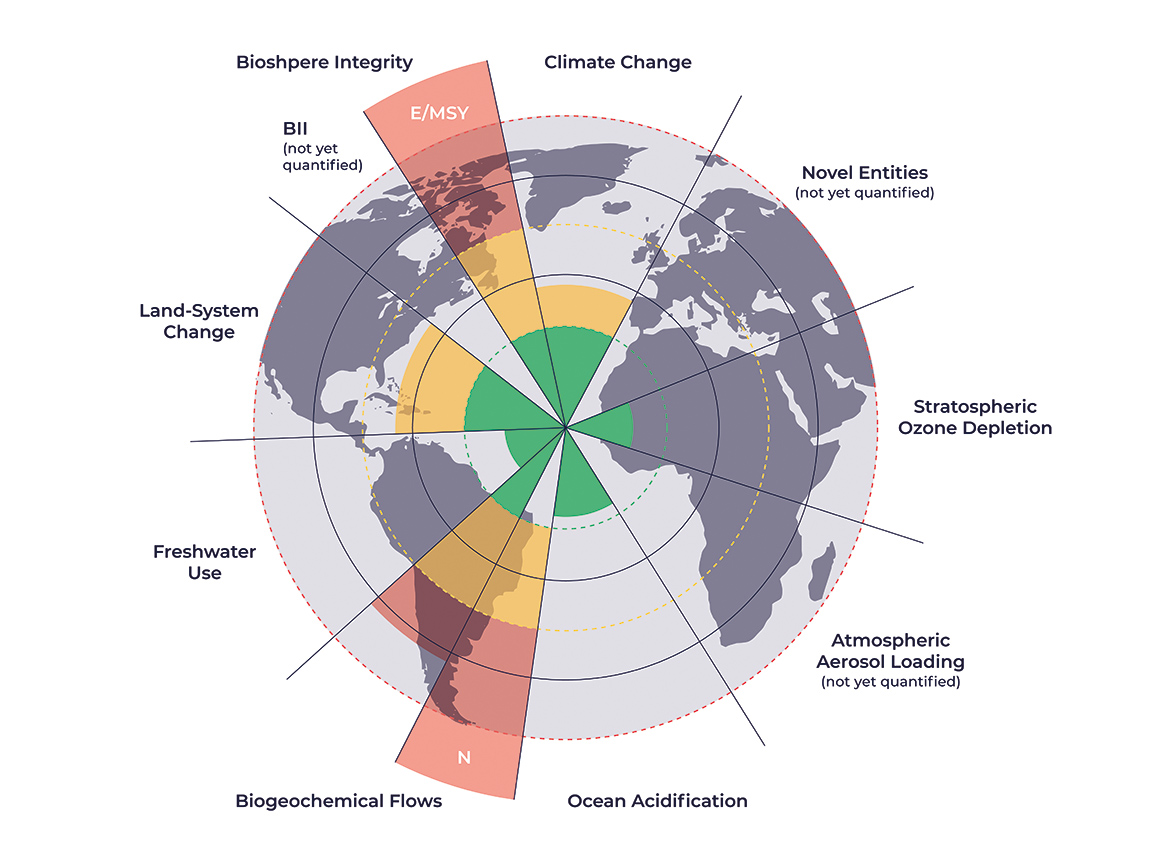

The Nine Planetary Boundaries concept represents the limits of planetary health signals we must not pass to ensure humanity can continue to develop and thrive for generations to come.

Hundreds of workable solutions to get to Net Zero

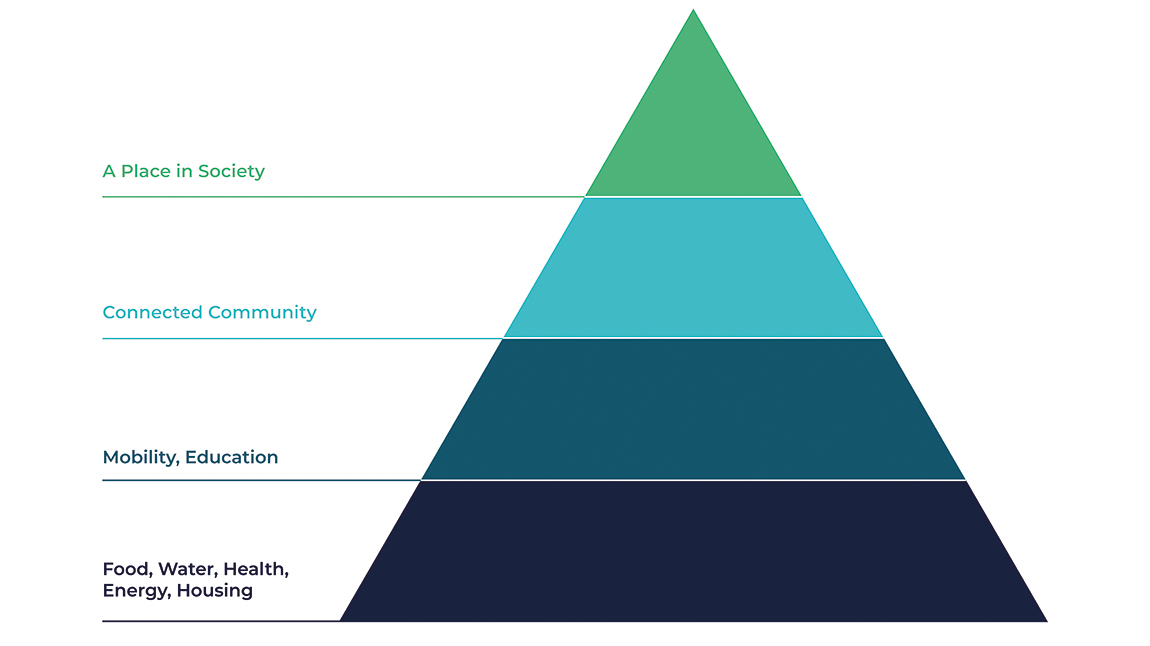

Larsen is very clear on one thing: to achieve gargantuan objectives like meeting net-zero before 2050, public wellbeing and prosperity must be at the heart of all solutions. “Many populations, for example in the global south, are not thinking about reducing their emissions – they are simply trying to survive, and in progressively extreme temperatures and inhospitable environments.” Inspired by economist Kate Raworth’s ‘Doughnut economics’ (pictured), the company aims to recommend solutions suites in line with the nine Planetary Boundaries, as well as meeting the basic resource needs of a population. It is vital that people’s needs are met in a sustainable way (represented by the inner social foundation ring), from access to food, energy and water, but also to equal rights and education for everyone, which will result “not just in top-down change implementation, but sustain a long-term and community-driven green transformation,” Larsen explains. “We need to ensure that, at a bare minimum, the solutions applied do not negatively impact the local population. That is why changes in London and France did not go as planned: local populations were detrimentally impacted. Climate PI’s recommendations for solutions suites will seek to ensure that people’s living standards are not lowered, or improve them,” she adds.

The hundreds of innovative solutions include nature-based, technology-based, regulatory and social solutions. Some may sound more familiar, such as wind and solar power technologies. Others are slightly less conventional, and yet research and testing show some of these are extremely effective tools to reduce emissions. Cows, for example, are some of the biggest methane emitters in the world, but field-testing has shown that feeding them seaweed reduces their methane emissions by up to 90 per cent. “This could be an invaluable solution in areas dependent on cattle farming,” Larsen explains. “This is a good example of how a shift in practices can help a local population maintain sources of income whilst reducing emissions.”

Larsen touches on another extremely important point: for many years now, people have been told to reduce their own individual emissions to combat climate change. This is an important piece of the puzzle to be sure, however, it is not quite as significant as we’ve all been led to believe. For instance, even if everyone on the planet stopped flying tomorrow, this would account for only around a 2.5 per cent cut in global emissions. If everyone drove an electric vehicle we would still only reduce emissions by 5 per cent – not to mention the emissions generated in manufacturing those vehicles. “This belief that the onus of reducing carbon footprints is squarely on individuals’ shoulders is a myth that was started by fossil fuel companies in the 1980s. It was a distraction technique and disinformation campaign to divert attention from the really problematic sources – their highly-polluting products,” Larsen explains.

This homing in on the wrong areas of societal systems is something Climate PI wants to help decision makers correct, but scaling these solution suites to the appropriate locations will take time. The firm first aims to maximise emissions reduction by focusing on cities, which account for 73 per cent of all emissions. “Cities are where The Climate PI aims to scale up its data collection points initially. The challenge is that not one city is alike – Paris is different to Los Angeles which is different to Amsterdam,” Larsen says. “Importantly, though, cities also have many similarities – the right datasets combined with innovative machine learning can tell us what these are, and which solutions can be used in another city, based on a model city’s success.” Larsen gives Amsterdam and Copenhagen as examples of cities where the same solutions could be employed – not just because they are similar sizes, but because of similarities in factors such as bicycle and public transport usage or political attitudes towards climate.

Finding the similarities between cities is no small task, and it will require providing the solutions recommendation engine with a (near) real-time supply of environmental intelligence. This includes geospatial data, ground-based sensors, tailored reports from local entities, etc. Repeating this process for every location is obviously not viable, and that’s where machine learning plays a major role. “By learning what works and what does not, it can identify which solutions are environmentally suitable for each location,” explains Larsen. “Take olivine (vulcanic) rock weathering, for example. AI could study beaches where this solution worked and identify which ones have the same potential.” By automating these kinds of processes, the Climate PI engine can map the path to sustainability in look-alike locations and scale up decarbonisation.

Mazlows Hierarchy of Needs. The Climate PI is based on the conviction that basic needs must be fulfilled for environmental solutions to become successful.

Carbon offsetting and carbon insetting

Another important distinction which The Climate PI wants to highlight are the differences between carbon offsetting and carbon insetting. Offsetting – where one company pays for carbon credits from another firm which has more renewable energy initiatives or reforestation projects – is an important aspect of getting to net-zero by 2050 and will unfortunately be the primary way most companies will achieve their net-zero targets. The Climate PI wants to encourage more meaningful climate action by companies so they address emissions sources directly within their value chain. Instead of trying to buy off the negative consequences of a firm’s supply chain through distant nature based solutions, carbon insetting aims to reduce emissions associated with the firm’s own supply chain. Danish fashion brand Ganni recently took the decision to divest from suppliers using coal-generated heat or electricity by 2025, and is also reducing waste by recycling its clothing fabrics. “Another good example of insetting is where companies commit to greening the cities where they are headquartered,” explains Larsen. “For example, HSBC is headquartered in London – a city which is currently experiencing unprecedented heat of over 40 degrees Celsius. HSBC has committed to net-zero by 2050, something which the firm should not be able to do with offsetting alone. It could change its supply chains, but it could also directly invest in green initiatives in its headquartered city of London. Similarly, BMW could make the profound decision to sponsor Munich’s decarbonisation. This will have a direct benefit to their employees, too.”

To help advise companies, cities and eventually entire countries on which solutions would have maximal impact, The Climate PI’s dashboard (pictured) will give key metrics for stakeholders to be able to measure the rate of success of their policies. “Plugging in the data to the dashboard would allow cities to see the rates at which these changes are being implemented, and the differences in air, land and water quality as a direct result of these investments. It’s the overall impact of all of the climate and sustainability investments that cities and citizens want to see – political accountability on an ongoing basis towards the net zero target,” Larsen says.

The PI dashboard.

Thinking big

The genesis story for Climate PI began as a result of another innovative big-data venture, which Larsen and one of her Climate PI cofounders Sarah-Louise Penhall were involved with three years prior to the company’s inception. Hired by the Indian government to employ machine learning to predict which solutions would have the highest impact for rejuvenating the notoriously polluted Ganges River, Larsen and her colleagues began to think about the idea of overlaying local population health data to understand impact from changes in the river’s health. They then began to dream of unleashing the potential of this technology onto a bigger stage. “We began brainstorming, and asked each other what this could mean for reducing emissions and tidying up our entire planet. We realised that this could be applied to so many different areas, because all of the data is out there, but it takes a machine (that domain experts have taught to be) smart enough to make millions of connections a second to make sense of it and apply it to the right areas.”

Cofounders of The Climate PI, Jennie-Marie Larsen [left] and Sarah-Louise Penhall [right] with Celine Cousteau [centre]. Cousteau is an environmentalist filmmaker who has supported the founders and functioned as an advisor on the importance of the knowledge of Indigenous Peoples when it comes to protecting and conserving biodiversity and natural habitats.

Three years after the ideas had initially begun to flow, and realising the potential of their vision, Larsen and Penhall found themselves on stage at a green technology conference in Monaco. Having made presentations and spoken to many different experts on how to get their idea off the ground, they caught the attention of one of the conference’s speakers. Celine Cousteau, environmentalist filmmaker and granddaughter of pioneering oceanographer Jacques Cousteau, approached Larsen with ideas. “Celine really believed in our vision, and we count her as an advisor and our first teacher on the importance of Indigenous People’s knowledge as stewards of 80 per cent of the world’s biodiversity,” Larsen explains. “She is committed to supporting the rights of the tribes of the Javari region in Brazil. Their territory is the size of Portugal, and there are many vital lessons that can be learned from how they manage the land. Celine has been helping the tribe to share lessons (that the Climate PI would read in data) about how this land is managed so sustainably.”

Feeding cows seaweed is one of the many examples of small but high-impact changes which can be implemented without negatively impacting jobs and income affecting jobs.

From there, the endorsements have continued to flow. One big seal of approval came recently from Karim Bouamrane, mayor of Parisian suburb Saint Ouen. Bouamrane intends to implement many sustainable changes to Saint Ouen, from efficient buildings and city farms to green education programmes and renewable energy. To do so, he will use the PI’s Sustainability Ratings Dashboard to help track and drive their path to net zero by measuring and predicting the impact of a suite of deployed climate/sustainability solutions. “We are absolutely thrilled to have Karim onboard, and we think this could build into an excellent symbiotic relationship – with the dashboard giving Karim insights on how the changes are working, and with us able to collect data to learn in a part of Paris which we could eventually scale up to Paris as a whole, and potentially other similar cities across the globe,” Larsen says.

Many new cities in Europe, North America and Brazil have already expressed interest in testing the PI’s Sustainability Ratings Dashboard. “We are thrilled to be working with so many trailblazers already, including the GUD (Global Urban Development) who are partnering with The Climate PI to provide the Sustainability Ratings Dashboard to support and drive the net zero transitions of their member cities,” says Larsen. The Climate PI will help fast forward the important climate and sustainability learning necessary for city decision makers to make efficient investments in climate solutions. “Very few political leaders have had the opportunity to gain real, in-depth climate education. They need help in this critical transition period. A solutions recommendation engine that provides impact prediction can give them a huge leg up,” says Dr. Marc Weiss, CEO of GUD.

This is how it will be for Climate PI’s team for some time, it seems – busy, exciting, challenging and transformative. Larsen agrees that it is an exciting time for the organisation: “Over 1,000 cities worldwide are committed to reaching net zero by 2050 and we can expect this number to grow exponentially. Our mission is to support and accelerate that process by sharing lessons of “tested and proven templates for transition” to the many cities who will make those same commitments,” she says and rounds off: There’s no time left for competition, the time has come for collaboration and the sharing of lessons – both the successes and the failures. Knowledge is the principal resource of the human race and it should be shared. “

Visit: www.fpi.earth for more information, or contact info@fpi.earth to get in touch.

The idea for The Climate PI arose as its founders were hired by the Indian government to employ machine learning to predict which solutions would have the highest impact for rejuvenating the notoriously polluted Ganges River.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Receive our monthly newsletter by email