Viniculture – a poster child for climate change adaptation

BY MIKE SCOTT | PHOTOS: JAS HENNESY & CO/CHRISTOPHE MARIOT

TED, a Naïo Technologies robot, is an autonomous mechanical weeding robot for vineyards and is part of a digital revolution in sustainable viticulture. TED automatically removes weeds around the vine plants meaning wineries no longer need to use herbicides.

Shaping the individual taste characteristics of all wines, climate conditions have always been essential to wine production. Mike Scott investigates how the viniculture industry is using high- and low-tech solutions to battle climate change and freak weather conditions.

If you think of wine, it is likely to conjure up images of partygoers sipping Champagne, a sommelier at a restaurant table or connoisseurs sipping different vintages at a tasting. Underneath all the glamour, the marketing and branding, though, at its heart, winemaking is farming – and like other farmers, winemakers are feeling the heat from climate change.

Wine has always been affected by climatic conditions, which along with the terroir – or the natural environment where vines are grown – helps to give particular wines their unique characteristics. And freak weather conditions – frost in the spring or heavy rain in the flowering season – can destroy a particular vintage.

At the same time, particular varieties are grown in certain regions because the conditions were best suited to them when they were planted – some of them decades ago. But all that is changing as the world warms.

Flocks of sheep have been introduced to the Hennesy vineyard to graze, conserve the grass and, at the same time, enrich the soil with organic matter.

No easy solutions

Extreme weather events are becoming more frequent and more severe, increasing the threat to harvests while the overall rise in temperatures will mean that it will become impossible to grow wine in some areas. In California, which in 2020 suffered its worst wildfires in modern history (as did Australia), wine growers are also having to contend with what Zurich, the insurance company, calls “one of the deepest megadroughts the region has seen in over 1,200 years”.

Meanwhile, the soil in vineyards – which is so central to the quality of the wine – is being depleted and degraded by higher temperatures and erosion. “Globally, about a third of soils are depleted,” says Philippe Schaus, president of Moët Hennessy. The company takes the issue so seriously that it organised the first World Living Soils Forum in Provence earlier this year.

The easiest solution to climate change is simply to move further north or south depending which hemisphere you are in to take advantage of cooler climes. But while winemakers in Chile and New Zealand have been doing that, and wine is now being grown in unlikely regions such as Tasmania, Wales and Denmark, it is not an option for some of the most famous wines, which are defined and tightly restricted by the Appellation system – the defining feature of Champagne, Rioja or Bordeaux wines is that they are grown in the regions whose name they bear.

“Wine is the highest-value production crop,” says Linda Johnson-Bell, founder of the Wine and Climate Change Institute. “It’s critical that wine-making becomes more sustainable.”

A conference on soils in Provence explores sustainable methods in viticulture. Photo: Grégoire d’Ablon

A natural defence

The industry is starting to do just that, from the vineyard to the vintner. Winemakers are deploying a range of technologies and techniques, both ancient and modern, to adapt. Moët Hennessy has announced plans to stop using herbicides, for example, as well as using more environmentally friendly packaging.

The company’s Chateau Galoupet rosé wine, made in Provence, is now sold in flat bottles made from recycled plastic collected from ecologically sensitive coastal areas. The bottles have a lower carbon footprint than glass ones. They are also both ten times lighter than glass bottles and take up 40 per cent less space, making them easier and more efficient to transport.

A number of vineyards have adopted agroforestry or regenerative agriculture techniques. While the traditional image of vineyards is of uniform rows of vines stretching out as far as the eye can see – and nothing else – many winemakers are now planting cover crops in between vines to move away from the monocultures created by planting only vines. Cover crops help to reduce soil erosion and to keep the soil aerated, as well as supplying nitrogen and other nutrients that improve the health of the vines, and ultimately yields. They also provide a habitat for birds and insects.

Some vineyards have animals wandering through the vines – in the Di Fillipo vineyard in Umbria and the Clos de Quarterons estate in the Loire Valley, both of which are organic producers – geese roam freely, eating weeds and pests and fertilising the soil.

Innovating to preserve

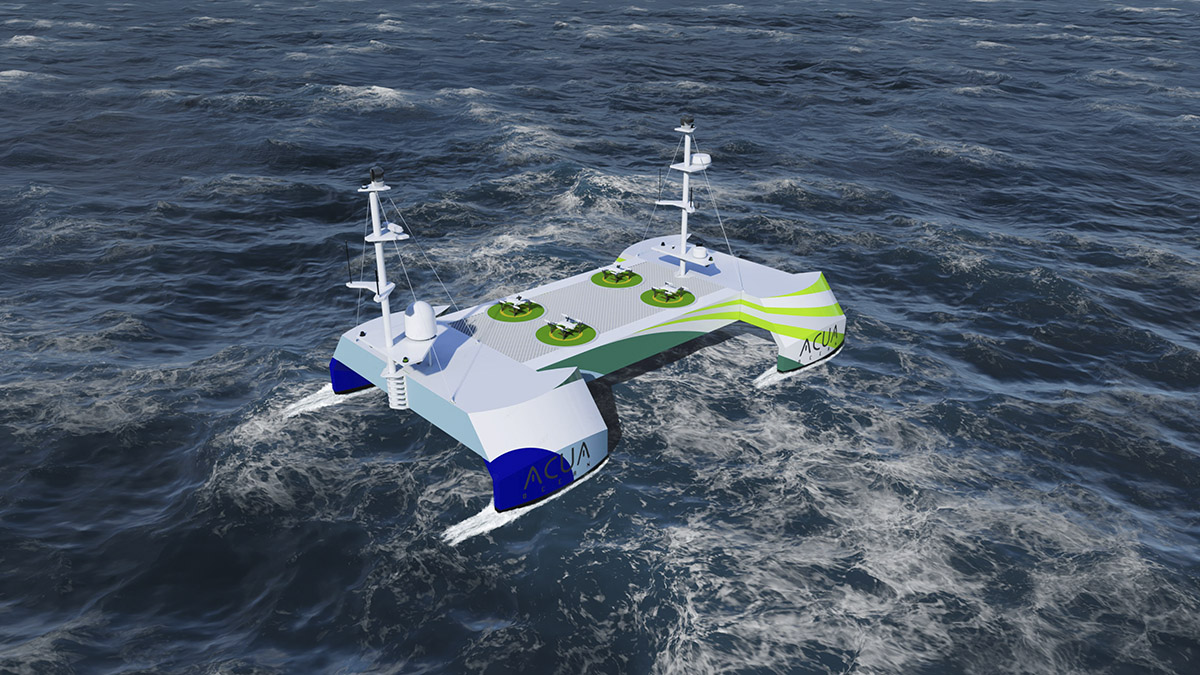

But the search for sustainability is not just about returning to centuries-old practices – technology is playing a key role as well. Winemakers are looking to use tools such as drones, the internet of things and artificial intelligence to address the challenges they face.

Drones are being used to do everything from deterring birds, to delivering pesticides and fertilisers, and to provide a wealth of information to vineyards. They can detect diseases, measure weed infestation, assess moisture levels and predict grape yields. By highlighting the ripeness and sugar levels of grapes, the images they provide can help winemakers decide the best time to harvest their grapes.

And many producers are using sensors in the soil to provide real-time updates, not just on temperature, rainfall and soil condition, but also incoming weather that may harm the vines. Start-ups such as Israel-based CropX are using sensors and software to collect data from above and below ground to help producers manage resources such as water, fertiliser and pesticides.

“Everything gets crunched in the cloud using very advanced machine-learning algorithms and AI to provide bottom-line insights to farmers and help them save on water, fertiliser and emissions, maximising their yield potential, thus becoming more environmentally sustainable,” said Matan Rahav, director of business development.

Another group, Deep Planet, offers AI tools to predict yield, maturity, soil moisture, disease, nutrients and soil carbon. The company’s VineSignal product helps growers to predict the best time to harvest their grapes, forecast the likely yield so they can plan their vintages and optimise irrigation so they use as little water as possible.

For higher value wines, sensors can also be used to provide traceability of the wines from vineyard to the consumer.

Changing mindset

Wine is a poster child for climate change adaptation, says Johnson-Bell. “It’s high-profile, known and loved throughout the world and grapes are the most delicate of fruits. What happens here will happen to other crops.”

A mix of technology and tradition will help the sector to adapt, she says, but in an industry with an 8,000-year history, “the greatest challenge to making viticulture more sustainable is changing mindsets. Investing in sustainable practices needs to be seen as an opportunity, not an obligation.”

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Receive our monthly newsletter by email